Summary of Wilhelm Liebknecht's 'No Compromise' (with Lenin's Preface)

How should socialists in a party use their position in bourgeois political bodies? When should a socialist party engage in electoral politics, and when should they abstain? When is it acceptable to make a compromise, and when does a compromise become unacceptable? Overall, what positive and negative lessons can be learned from the theory and practice of Kautsky and Liebknecht and the SPD, Lenin and the RSDLP, and (a bit) from the independent socialist Alexander Millerand in France?

Liebknecht’s work is important for the RSDLP in the context of the elections to the second Duma. (Elections begin in late 1906 and the Duma runs from February to June of 1907).

The RSDLP can learn from Liebknecht on the question of forming agreements with rival parties. Here in Russia, we are concerned about forming a block with the Cadets. The cadets (moderate constitutional democrats - CD = ‘ka’ ‘deh’) were in the majority during the first duma. They were originally more to the left but eventually came to support a constitutional monarchy after the revolution faded in 1906.

There are many inside and outside the RSDLP who think we should form a block with the cadets. Plekhanov, a leading Menshevik. Sergei Prokopovich (a former Social Democrat cited by Lih in chapter one) (“renegade” b/c he was in the RSDLP but left in 1899 after he was influenced by Berstein and the Fabians towards economism), and the newspaper Tovarishch (The Comrade), an unofficial organ for the Left Cadets, all agree on this point.

The Mensheviks say the anti-democratic extremist monarchist Black Hundreds are the real threat, and unity with the Cadets is necessary to defeat them in the Duma elections.

But, it’s wrong to say the Cadets fundamentally oppose the Black Hundreds in the name of democracy. The Cadets are principally undemocratic: they were the first to adapt themselves to the changed revolutionary circumstances (renouncing the parliamentary republic, entering the First Duma) in contrast to the actions of real a revolutionary party (that adapts itself to the conditions of a declining revolutionary movement only begrudgingly and continues to champion the overthrow of tsarism). The RSDLP must combat all forces, says Lenin, that does not oppose the monarchy.

In the context of Germany, Liebknecht states that the establishment of new anti-socialist laws (1878-1891) would be the greater evil (many in the SPD disagree with this). The Mensheviks, too, would have the Bolsheviks make compromises in the name of combatting The Black Hundreds “greater evil.”

Liebknecht warns us: an electoral agreement with a false friend is the greater evil because it weakens the class consciousness of the working class. An internal enemy sows confusion and eats away from the inside. One is reminded of Marx in the 1850 address to the Communist League: “The progress which the proletarian party will make by operating independently in this way is infinitely more important than the disadvantages resulting from the presence of a few reactionaries in the representative body.”

Allies can be useful in parliament, but one must be sure the “ally” is actually what they appear to be. Agreements can be tactically useful, but one must not endanger the long-term goals of the working-class party.

Liberalism is treacherous: the working class must lead the democratic revolution in Russia, say the Bolsheviks, not ally with the liberals or make concessions to them for fear of “scaring them away.” Plekhanov and Prokopovich might have good intentions in their desire to avoid a Black Hundreds majority, but they would sacrifice Social Democracy for that end, and the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

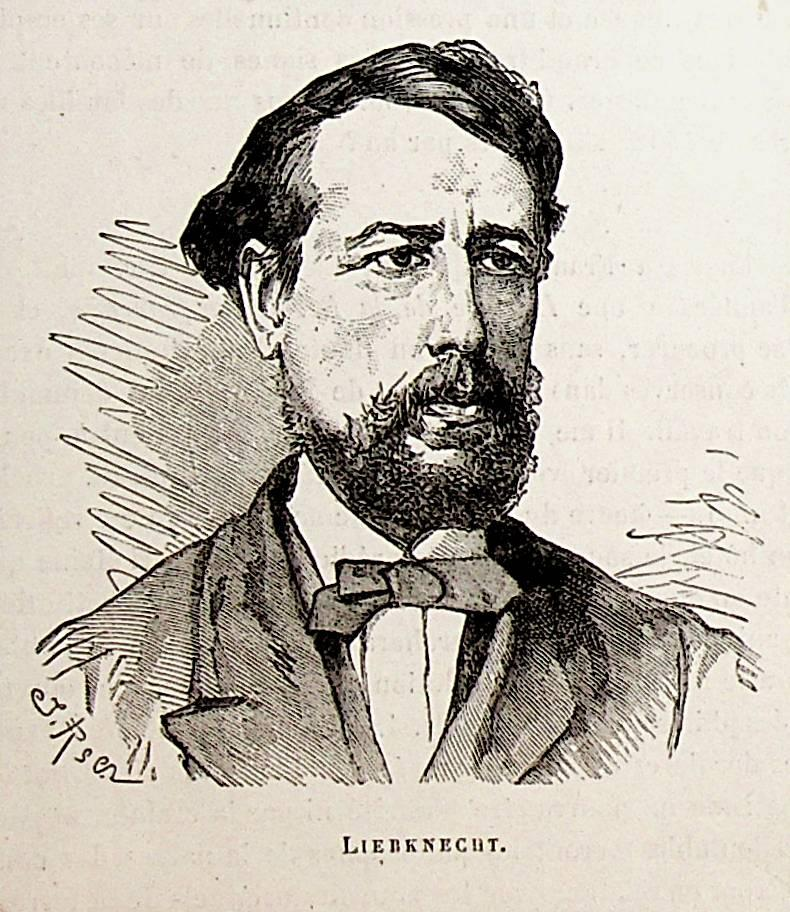

No Compromise - No Political Trading

In 1899, one year before his death, Liebknecht was asked to write a pamphlet for the SPD in order to clarify where the party stands on parliamentary activity. That same year, two events had taken place that raised concern. In Germany, the leaders of the Bavarian Social Democrats entered into an out-and-out alliance with the Liberal party during the Bavarian legislative elections (a political “cow-trade”). While the Southern German party often violated party rules, the events of that were remarkable for their complete honesty and boldness. The Bavarian Legislative elections followed the extremely undemocratic Prussian three-tiered voting rules and, as Liebknecht later explains, a Party resolution forbid electoral participation in legislative elections on that basis, expressly because the only way to win an election would be to form an alliance with a bourgeois party. Participation in the Reichstag was allowed because suffrage rules were more democratic and thus a victory was conceivable without entering into a formal alliance with another party. Also in 1899, French independent socialist (he belonged to no party) Alexandre Millerand accepted a cabinet position in the government of prime minister Waldeck-Rousseau. Also in government was the “butcher” of the Paris Commune, the Marquis de Galliffet.

Liebknecht produced this pamphlet in order to explain SPD tactics related to compromises and alliances in elections, as well as the consequences of sacrificing party principles.

Party law:

The Party resolution passed at the Cologne convention in 1893 (called by Bernstein) stated that party members should not participate in the Prussian legislature (Bavaria was a part of Prussia after 1870) because it was impossible to do so with any prospect of success without making compromises with other parties. During the 1897 Hamburg convention, a resolution was passed stating that SPD members could run in Prussian legislative elections but should not enter into compromises and alliances. A conflict ensued over what constitutes a compromise, and the confusion was so great that the Stuttgart convention of 1898 could only pass a semi-ambiguous emergency measure reiterating the resolution of the Hamburg convention. Compromises in violation of party principles continue to be made, especially in the South.

Proletarian socialism:

The SPD should depend exclusively on the strength of the party. This principle was held until 1893 when the discussion around winning elections to the Prussian legislature began. What changed? Why are the party principles of class independence losing strength as seen in interest in contending for seats in the Prussian legislature? First, comrades have forgotten the truly undemocratic nature of the Prussian three-tiered system. Second, there is a growing interest in deserting the Party platform of class struggle (see Bernstein, who switched to supporting Prussian legislative participation after opposing it in 1893).

State capitalism:

What makes Germany unique from some other European countries? We don’t live in a democracy and we have no real liberal party. The SPD is the lone champion of basic democratic rights. As a result, everyone interested in a democracy tends to gravitate towards the SPD regardless of how they interpret the socialist program. The party might grow in size and influence, but the result is greater confusion about the principles of socialism. The party grows weaker when its ranks are swollen by “philanthropic humanitarian radicalism” which thinks that state capitalism is socialism. The more we are accepted by certain elements of German society, the more we must resist becoming just another political party in Germany. We are a Social Democratic Party because we believe socialism and democracy are inseparable.

Bismarck:

We must heighten the quarrels and conflicts between the ruling forces in Germany, not side with one against the other in order to win certain favors ( a la Lassalle, who died in 1864).

What is a compromise?:

A compromise is not a concession of theory to practice. The whole of human history is the new being birthed from and through the old in a confusing, confused, and messy process, therefore the idea of some clean break from the past is a fallacy. Politics, like life, is about compromise.

The SPD engages in political warfare while in parliament, and this means sometimes voting with other parties. We work with the tools at hand.

What we don’t do is enter agreements that in any way surrender our principles. This is a tricky point because people in the party who want to ally with the Progressive party in the Prussian legislature don’t want to surrender our principles either. Yet, their actions would change our relationship with bourgeois parties in a manner injurious to Social Democracy.

Socialism and ethics:

Socialism is the recognition of the class struggle and the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat. If this understanding is lost, if the foundation in class understanding is forgotten and the party is removed from that struggle, then Social Democracy and the working class movement is dealt a devastating blow. Small cranks grow larger over time, and the most devastating cracks are created by “friends” on the inside. Social Democracy can retain its foundation in the Erfurt Program if it always calls a spade a spade; if it never loses sight of its true friends and true enemies while going about its day-to-day business; and if it remains true to its aims (the final goal is everything, not “nothing” ala Bernstein). Will we remain a socialist party or cross the rubicon of class struggle and become the left wing of bourgeois democracy?

Theoretical differences:

We recognize no higher authority than science. Therefore, all theoretical differences are welcome in the SPD.

“No socialist has the right to condemn attacks on the theoretical ideas of the Marxian teachings or to excommunicate anyone from the party because of such attacks. But it is different when those attacks imply a complete overturning of our conception of society, as is the case with Bernstein. Then, vigorous defense is in order.”

Workers, the ranks and file of the party, haven’t read Bernstein’s work. They don’t care about his ideas so long as they exist in the realm of theory. But participation in the Prussian elections and the cow trading in Bavaria is a different matter. People pay attention when it’s a matter of party action and principle (this is a good thing!). It’s all well and good to talk about the party platform in theory, but what about in practice, when push comes to shove?

The resolution of the 1897 Hamburg convention (allowing for participation in the Prussian elections) was a close call (saved by the final line of text condemning alliances): we nearly put in our lot with the bourgeois parties. We must remember that the Stuttgart emergency resolution a few years later did not repudiate the Hamburg resolution. Violations of these convention documents are made, but they remain violations of the party principle (ie, they go against official policy).

We are a peculiar people:

Social democracy’s power in German society comes not from the number of political representatives but from its ability to mobilize the working class and draw an increasing number of workers into its ranks. It’s for this very reason that bourgeois parties want to form alliances with us! Social democracy represents all people who suffer (see Lenin in WITBD regarding a tribune of the people). People come to us not because they know our theory or because they have any conception of “capitalism” or “socialism.” They come because they know we are not the oppressors and because they know we can help them. They know this because we stand outside the ranks of the bourgeois parties. We are outsiders where it matters most; we are peculiar people.

The inclined plane:

Once you make one concession it's hard to stop. People laugh at us for “crying wolf” like every little thing we do is some kind of disastrous compromise. Well, what if the wolf is already among us? Furthermore, socialists are the ones who compromise only with the most resistance and most scorn; it’s not something to be taken lightly. We don’t tread gladly on the inclined plain because once you stumble you fall fast.

Alexandre Millerand:

Socialism is increasingly an international affair, and therefore it is my duty to comment on

international matters that concern the class. The bourgeois is intelligent. It will take foolish “socialists” (Millerand) into its government to use them as shields. The socialist in government paralyzes the socialist parties (how are they to attack a government that is now nominally “socialist”?) and serves as a fall-guy for all reactionary policies (if they didn’t actively support them); oh, the socialists did it (see the SPD taking power from the German High Command and taking the poison apple of surrender).

The situation in France:

In the context of popularly elected bodies (lower house or chambers, like the House and Representatives or the Reichstag), what is called a compromise is often just a momentary “coming together under the result of certain conditions” that, crucially, entails no obligations.

It is incorrect to call the presence of socialists in these bodies a “compromise.” Rather, their presence is the result of socialists taking advantage of, and forcing themselves in through the vote of the people, the only popularly elected body available. The SPD wouldn’t be in the Reichstag if the government could help it (and for about 13 years they thought they could help it, but then learned they could not).

Independent Action:

I took a lot of heat for saying a new anti-socialist law wouldn’t be as bad as working with the bourgeois parties in Prussia. Are we going to let fear dictate our principles? (See Engle’s critique of the Erfurt Program for excluding the Republic).

Comments

Post a Comment