A Russian and West Indian in Revolutionary Sudan

Born are the beautiful children, hour by hour

with brightest eyes,

and loving hearts you have bestowed upon

fatherland, they will come, for bullets aren't the seeds of life.

- Mahjoub Sharif, Born are the Beautiful Children

The Imprisoned Poet

Famed activist and poet Mahjoub Sharif was imprisoned for the first time in 1970 by the National Revolutionary Command Council, chaired by the soon-to-be 15-year president of Sudan, Gaafar Nimeiry. The recipient of a Master’s Degree in Military Science from Fort Leavenworth, Nimeiry retained power until 1985, when one of many military coups (succeeded by one of many Transitional Military Councils) led to the rise of Ahmad Al-Mirghani in what is considered the last democratic election in the country’s tumultuous political history.

Enter (via yet another military coup) the first of several starring characters: Omar al-Bashir, chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation from 1989 to 1993, then president from 1993 until April 11 of this year. Under al-Bashir, hundreds of government opponents were imprisoned, including Mahjoub Sharif. Trade unionists were arrested, tortured, and killed. Journalists and lawyers were harassed and discourse crushed. According to Amnesty International, “members of virtually every sector of Sudanese society in both northern Sudan and the war-torn south suffered human rights violations.”

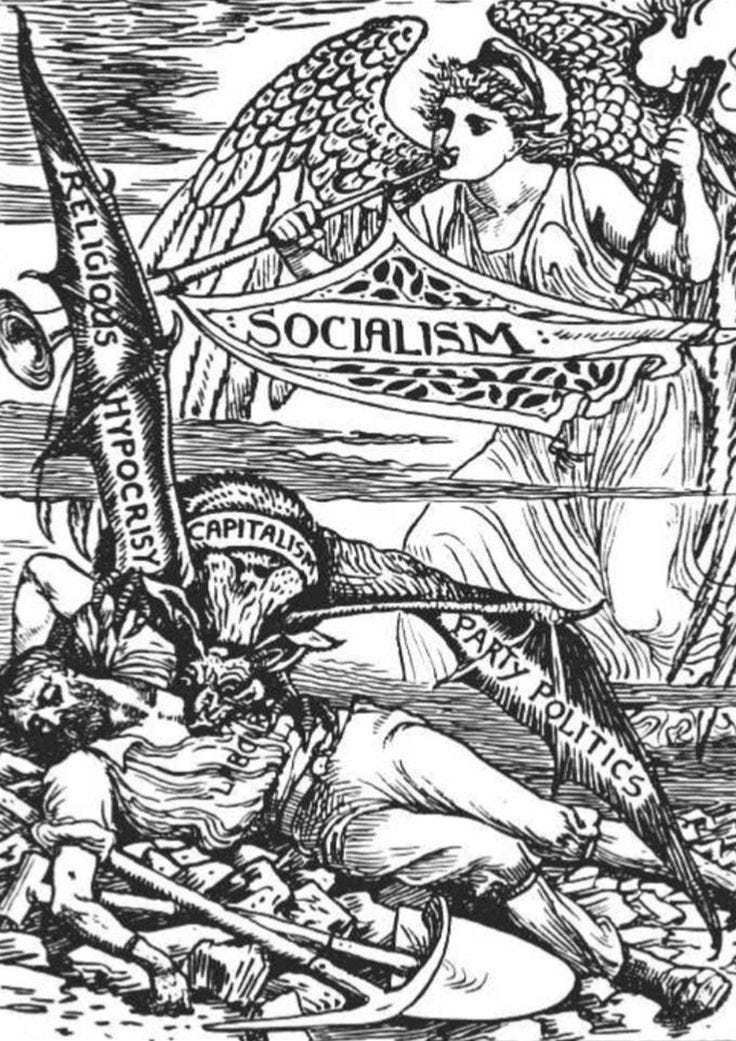

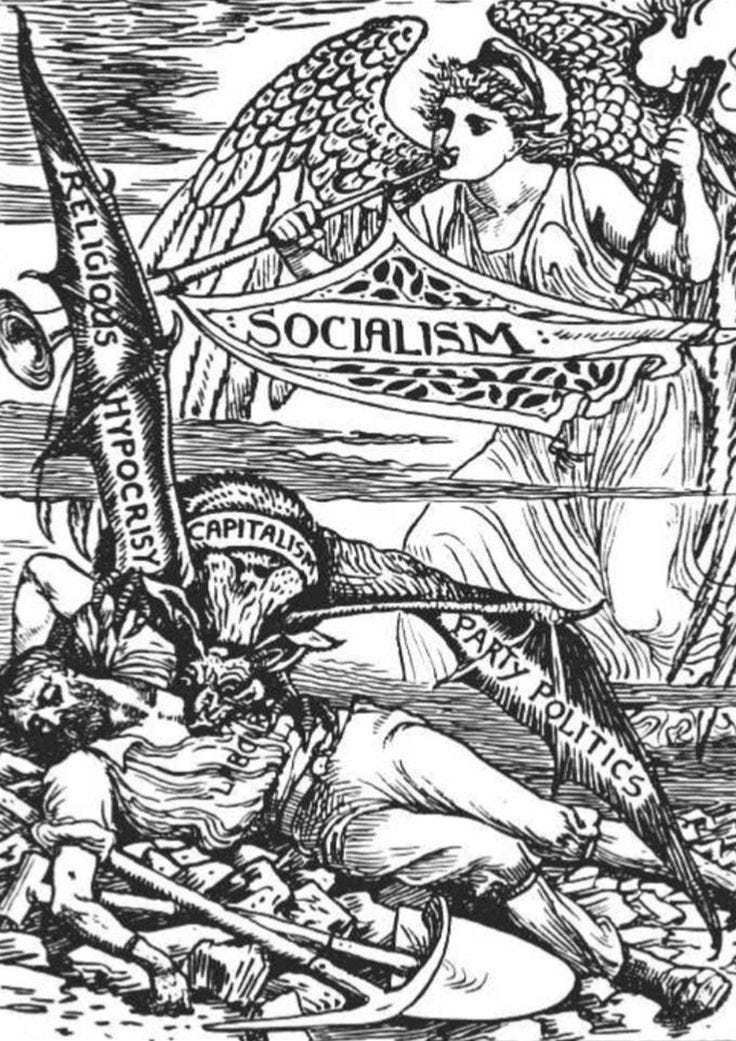

As Tariq Ali describes, the government “made a generation in its own image, borrowing the Islamic curriculum of the Muslim Brotherhood…Religious thought suffused every aspect of the state, masking the corruption of a class and a parasitic capitalism that stole the resources and the riches of the country.”

But somehow, someway, contradictions are always resolved. The mole of history never ceases to burrow, now and then making its presence known. Just ask the former president of Turkey Zine Ben Ali, the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, or ex-Yemeni ruler Ali Abdullah Saleh. (Though pushed to the brink, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad remains in power, aided by Russian bombs and chants of “Assad or we burn the country”).

The Fall of al-Bashir

In December of last year, millions of people began filling the streets across Sudan in response to growing inflation and the tripling of the price of bread. Like so many African nations, Sudan is held hostage by debt from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and forced to implement neoliberal austerity measures as a result.

One grievance has built on another, with decades of history of exploding in a matter of hours. While al-Bashir and his hangers-on lived in luxury, the country slipped farther into misery. As of 2018, at least 80 percent of the Sudanese population lives on less than $1 per day, with some 2.5 million children suffering from acute malnutrition. An estimated 1.2 million refugees and asylum seekers live alongside nearly 2 million internally displaced persons following Sudan’s decades of internal conflicts and droughts.

In a bid to stabilize the country and dissuade a growing popular movement, a military junta under the all-too-familiar name of the Transitional Military Council (TMC) ousted al-Bashir and seized power on May 11.

The TMC is supported by various capitalist powers including the United States, Saudi Arabia, China (whose companies control 75 percent of Sudan’s oil and natural gas), and Russia - the latter-two countries voting to block a UN resolution condemning recent attacks on protestors. (The last time al-Bashir left his veritable fiefdom, he traveled aboard a Russian airplane on his way to visit the mass murderer Bashar al-Assad and grovel for his return to the Arab League).

The military has refused to send al-Bashir to the International Criminal Court, as his alleged crimes - including crimes agaisnt humanity and genocide - are their crimes as well.

Yet the masses, composed of students, the unemployed, women, youth, and other various middle and working class elements, did not leave the streets. The decision to stay on the streets and protect occupied public space is one of the key lessons learned from the Arab Spring.

Also of note is the role of women, forever embodied by Alaa Salah standing atop a car with her finger raised skyward, speaking to a crowd largely made up of women. A practitioner of Sharia Law, al-Bashir’s regime is known for its repression of women. Representing only 18 percent of the wage labor force, women have yet to ‘achieve’ even the honor of exploitation within the capitalist market.

Revolution and Counter-Revolution

Facing mass pressure, the TMC agreed to a prolonged transition to civilian rule. But the Sudanese military has no interest in popular democracy, wanting nothing more than to replace al-Bashir, himself a former General, with another military man. Negotiations between the military and civilian bodies have since deteriorated over leadership positions within the proposed transitional council and increasing violence against protestors.

Also of note is a divide (the extent of which is not entirely clear) within the military, between hardline supporters of al-Bashir, followers of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) and Salah Gosh (now considered the most powerful man in Sudan), and more moderate elements disconcerted by the increasing violence. There are reports that certain groups of officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers joined the crowds in Khartoum and protected them from the NISS and the police.

What can only be described as a counter-revolution began on June 3. Security forces led by the notorious Rapid Support Force (also deployed as part of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen) and their commander and deputy leader of the TMC, Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan, opened fire on protesters in Khartoum, killing over 100. At least 40 bodies - some with stones tied to their legs - were thrown into the murky waters of the nearby Nile. Snipers shot people with cameras and soldiers disposed of rescuers execution-style. Nurses were raped, doctors beaten, and hospital and schools peppered with machine-gun fire. Protesters chanted, “You’ll have to kill us all.”

In response, millions heeded calls from the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) and the Forces for Declaration of Freedom and Change (FDFC) for a general strike. On June 10, life in Khartoum ground to a standstill as millions of residents withheld their labor power. Makeshift barricades of brick and stone appeared in the streets. “The roadblocks prevented me from reaching the market to buy vegetables," explained one street vendor. “This will impact my income, but when I look at these youngsters who are on the streets since six months, I'm not angry even if I lose my income.”

Fanon and the Pitfalls of National Consciousness

On January 1, 1956, Sudan achieved independence from a British colonial rule that had lasted (with the help of Egypt) since the 1830s. The struggle against colonization that swept the African continent promised many things for many different sections of society. Most alluring of all were the declaration of freedom, equality, and liberal democracy for the historically marginalized and exploited. And yet the majority of Sudanese – alongside the majority of Africans – still suffer.

Born in the French territory of Martinique, Frantz Fanon knew a thing or two about colonialism. Published months before his death, his exquisite work, The Wretched of the Earth, serves as a warning to the poor and working class within fledgling independence movements against the national bourgeoisie posing as allies. The African middle class, explains Fanon, is incapable of fulfilling its “historic role of the bourgeoisie.” (One hears the influence of Karl Marx in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, who wrote that the middle class must in fact always misunderstand its historic role in order to act on the grand stage of history).

Across Africa, writes Fanon in his section on The Pitfalls of National Consciousness, “the battle against colonialism does not run straight away along the lines of nationalism.”

Trotsky and the Theory of Permanent Revolution

In imagining a path forward in contemporary Sudan, the ideas of Frantz Fanon must be reinforced by those of Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Though a variation of the term was first used by Karl Marx in 1850 – “It is our interest and our task to make the revolution permanent…Not only in one country but in all the leading countries of the world” – the theory of permanent revolution is most closely associated with Trotsky. Indeed, Marx’s ideas of permanent revolution make up only half of those put forward by Trotsky in the context of early 20th century revolutionary Russia and echoed by Fanon some 50 years later during decolonization.

Trotsky was observing the combined and uneven development of Russia, in which a mostly feudal population coexisted alongside some of the most developed industrial pockets in the world. The economic development of Russia – that is, its late arrival to the stage of global capitalist development and the country’s subordination to the needs of global capital – was such that the bourgeoisie (remember Fanon?) could not play a progressive role in history: therefore, a more linear road to socialism through developments within a bourgeois revolution was out of the question.

“The incapacity of the bourgeoisie for political action,” wrote Trotsky

Crucially, the entire project hinges on the permanency of the revolution in a second sense: its ability to spread to countries outside of Russia. Decades before Stalin, Trotsky understood that socialism in one country was impossible. The workers’ movement is international, or it is nothing.

The necessity of a planned economy

Global capital, forever bound to its vampire-like task of consuming the lifeforce of the Sudanese people and the country’s natural resources, would like nothing more than a “free” and “stable” victim. Freedom and stability, of course, measured by the extent to which the country is malleable to the capitalist market. A typical solution put forward by a more liberal wing of the capitalist ideologs is exemplified in a proposal by Peter Woodward, who states that in order to bring stability to Sudan, a post-Bashir government must “clean up corruption; revive small-scale agriculture in the regions; restore health and education services; and attract investment for productive jobs for underemployed, educated young people who have been the backbone of the uprising.”

Yet, Woodward and his ilk live in a fantasy. What social force does Woodward imagine will bring about this transformation? A benevolent military? A (nonexistent) Sudanese bourgeoisie? The only force capable of transforming the Sudanese economy to meet the needs of the people is the Sudanese working class (80 percent of which is based in agriculture). Attracting investment means crushing labor and continuing to exploit natural resources. A workers’ government, in alliance with an international revolutionary movement, could refuse the dictates of austerity (à la Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso) and create planned economy designed to meet the needs of the African people - something the capitalist market is incapable of doing.

Independent class struggle

When history is written as it out to be written, it is the moderation and long patience of the masses at which men will wonder, not their ferocity.

- C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins

What the masterful Trinidadian socialist C.L.R. James wrote about the slaves of Haiti can be applied to the people of Sudan – just as it can be applied to the working class in the United States, China, and those laboring under capitalism in every corner of the globe. History promises nothing (some might add, except pain), but it does offer lessons and reveal trends.

What, then, can we learn from history as analyzed by a West Indian and Russian exile? The theory of permanent revolution would seem to be alive and well. It is crucial in understanding the revolutionary experience of less-developed, formerly colonized countries around the world. Neither the national bourgeoisie nor the military have anything to offer the masses of Sudan. If dictatorial rule is to fall, then socialism is the only way forward. No salvation lies in robust African capitalism – there is no freedom under wage slavery.

Perhaps most importantly, the Sudanese revolution must spread like wildfire! We repeat: The workers’ movement is international, or it is nothing. The struggle for freedom and an end to oppression in Sudan is the same fight waged in the streets of Algeria and Syria, the same struggle in Palestine and Ferguson, Missouri. Patient no longer, the ferocity of the masses will be truly astounding.

with brightest eyes,

and loving hearts you have bestowed upon

fatherland, they will come, for bullets aren't the seeds of life.

- Mahjoub Sharif, Born are the Beautiful Children

The Imprisoned Poet

Famed activist and poet Mahjoub Sharif was imprisoned for the first time in 1970 by the National Revolutionary Command Council, chaired by the soon-to-be 15-year president of Sudan, Gaafar Nimeiry. The recipient of a Master’s Degree in Military Science from Fort Leavenworth, Nimeiry retained power until 1985, when one of many military coups (succeeded by one of many Transitional Military Councils) led to the rise of Ahmad Al-Mirghani in what is considered the last democratic election in the country’s tumultuous political history.

Enter (via yet another military coup) the first of several starring characters: Omar al-Bashir, chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation from 1989 to 1993, then president from 1993 until April 11 of this year. Under al-Bashir, hundreds of government opponents were imprisoned, including Mahjoub Sharif. Trade unionists were arrested, tortured, and killed. Journalists and lawyers were harassed and discourse crushed. According to Amnesty International, “members of virtually every sector of Sudanese society in both northern Sudan and the war-torn south suffered human rights violations.”

As Tariq Ali describes, the government “made a generation in its own image, borrowing the Islamic curriculum of the Muslim Brotherhood…Religious thought suffused every aspect of the state, masking the corruption of a class and a parasitic capitalism that stole the resources and the riches of the country.”

But somehow, someway, contradictions are always resolved. The mole of history never ceases to burrow, now and then making its presence known. Just ask the former president of Turkey Zine Ben Ali, the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, or ex-Yemeni ruler Ali Abdullah Saleh. (Though pushed to the brink, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad remains in power, aided by Russian bombs and chants of “Assad or we burn the country”).

The Fall of al-Bashir

In December of last year, millions of people began filling the streets across Sudan in response to growing inflation and the tripling of the price of bread. Like so many African nations, Sudan is held hostage by debt from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and forced to implement neoliberal austerity measures as a result.

One grievance has built on another, with decades of history of exploding in a matter of hours. While al-Bashir and his hangers-on lived in luxury, the country slipped farther into misery. As of 2018, at least 80 percent of the Sudanese population lives on less than $1 per day, with some 2.5 million children suffering from acute malnutrition. An estimated 1.2 million refugees and asylum seekers live alongside nearly 2 million internally displaced persons following Sudan’s decades of internal conflicts and droughts.

In a bid to stabilize the country and dissuade a growing popular movement, a military junta under the all-too-familiar name of the Transitional Military Council (TMC) ousted al-Bashir and seized power on May 11.

The TMC is supported by various capitalist powers including the United States, Saudi Arabia, China (whose companies control 75 percent of Sudan’s oil and natural gas), and Russia - the latter-two countries voting to block a UN resolution condemning recent attacks on protestors. (The last time al-Bashir left his veritable fiefdom, he traveled aboard a Russian airplane on his way to visit the mass murderer Bashar al-Assad and grovel for his return to the Arab League).

The military has refused to send al-Bashir to the International Criminal Court, as his alleged crimes - including crimes agaisnt humanity and genocide - are their crimes as well.

Yet the masses, composed of students, the unemployed, women, youth, and other various middle and working class elements, did not leave the streets. The decision to stay on the streets and protect occupied public space is one of the key lessons learned from the Arab Spring.

Also of note is the role of women, forever embodied by Alaa Salah standing atop a car with her finger raised skyward, speaking to a crowd largely made up of women. A practitioner of Sharia Law, al-Bashir’s regime is known for its repression of women. Representing only 18 percent of the wage labor force, women have yet to ‘achieve’ even the honor of exploitation within the capitalist market.

Revolution and Counter-Revolution

Facing mass pressure, the TMC agreed to a prolonged transition to civilian rule. But the Sudanese military has no interest in popular democracy, wanting nothing more than to replace al-Bashir, himself a former General, with another military man. Negotiations between the military and civilian bodies have since deteriorated over leadership positions within the proposed transitional council and increasing violence against protestors.

Also of note is a divide (the extent of which is not entirely clear) within the military, between hardline supporters of al-Bashir, followers of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) and Salah Gosh (now considered the most powerful man in Sudan), and more moderate elements disconcerted by the increasing violence. There are reports that certain groups of officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers joined the crowds in Khartoum and protected them from the NISS and the police.

What can only be described as a counter-revolution began on June 3. Security forces led by the notorious Rapid Support Force (also deployed as part of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen) and their commander and deputy leader of the TMC, Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan, opened fire on protesters in Khartoum, killing over 100. At least 40 bodies - some with stones tied to their legs - were thrown into the murky waters of the nearby Nile. Snipers shot people with cameras and soldiers disposed of rescuers execution-style. Nurses were raped, doctors beaten, and hospital and schools peppered with machine-gun fire. Protesters chanted, “You’ll have to kill us all.”

In response, millions heeded calls from the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) and the Forces for Declaration of Freedom and Change (FDFC) for a general strike. On June 10, life in Khartoum ground to a standstill as millions of residents withheld their labor power. Makeshift barricades of brick and stone appeared in the streets. “The roadblocks prevented me from reaching the market to buy vegetables," explained one street vendor. “This will impact my income, but when I look at these youngsters who are on the streets since six months, I'm not angry even if I lose my income.”

Fanon and the Pitfalls of National Consciousness

On January 1, 1956, Sudan achieved independence from a British colonial rule that had lasted (with the help of Egypt) since the 1830s. The struggle against colonization that swept the African continent promised many things for many different sections of society. Most alluring of all were the declaration of freedom, equality, and liberal democracy for the historically marginalized and exploited. And yet the majority of Sudanese – alongside the majority of Africans – still suffer.

Born in the French territory of Martinique, Frantz Fanon knew a thing or two about colonialism. Published months before his death, his exquisite work, The Wretched of the Earth, serves as a warning to the poor and working class within fledgling independence movements against the national bourgeoisie posing as allies. The African middle class, explains Fanon, is incapable of fulfilling its “historic role of the bourgeoisie.” (One hears the influence of Karl Marx in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, who wrote that the middle class must in fact always misunderstand its historic role in order to act on the grand stage of history).

Across Africa, writes Fanon in his section on The Pitfalls of National Consciousness, “the battle against colonialism does not run straight away along the lines of nationalism.”

For a very long time the native devotes his energies to ending certain definite abuses: forced labour, corporal punishment, inequality of salaries, limitation of political rights, etc. This fight for democracy against the oppression of mankind will slowly leave the confusion of neo-liberal universalism to emerge, sometimes laboriously, as a claim to nationhood. It so happens that the unpreparedness of the educated classes, the lack of practical links between them and the mass of the people, their laziness, and, let it be said, their cowardice at the decisive moment of the struggle will give rise to tragic mishaps. National consciousness, instead of being the all-embracing crystallization of the innermost hopes of the whole people, instead of being the immediate and most obvious result of the mobilization of the people, will be in any case only an empty shell, a crude and fragile travesty of what it might have been.He continues in wonderful Fanonian prose.

In an under-developed country an authentic national middle class ought to consider as its bounden duty to betray the calling fate has marked out for it, and to put itself to school with the people: in other words to put at the people’s disposal the intellectual and technical capital that it has snatched when going through the colonial universities. But unhappily we shall see that very often the national middle class does not follow this heroic, positive, fruitful and just path; rather, it disappears with its soul set at peace into the shocking ways – shocking because anti-national – of a traditional bourgeoisie, of a bourgeoisie which is stupidly, contemptibly, cynically bourgeois.And concludes with a final barb.

Seen through its eyes, its mission has nothing to do with transforming the nation; it consists, prosaically, of being the transmission line between the nation and a capitalism, rampant though camouflaged, which today puts on the masque of neocolonialism. The national bourgeoisie will be quite content with the role of the Western bourgeoisie’s business agent, and it will play its part without any complexes in a most dignified manner.Months before his death, Fanon foresaw the entire sad history of the African continent post-independence. Liberté, Equalité, Fraternité, the watchwords of the Enlightenment, face an insurmountable obstacle in the form of capitalist social relations. Fooled by the seductive but hollow promises of nationalism, the masses of Sudan – the masses of African – have been betrayed by their class enemies at every turn.

Trotsky and the Theory of Permanent Revolution

In imagining a path forward in contemporary Sudan, the ideas of Frantz Fanon must be reinforced by those of Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Though a variation of the term was first used by Karl Marx in 1850 – “It is our interest and our task to make the revolution permanent…Not only in one country but in all the leading countries of the world” – the theory of permanent revolution is most closely associated with Trotsky. Indeed, Marx’s ideas of permanent revolution make up only half of those put forward by Trotsky in the context of early 20th century revolutionary Russia and echoed by Fanon some 50 years later during decolonization.

Trotsky was observing the combined and uneven development of Russia, in which a mostly feudal population coexisted alongside some of the most developed industrial pockets in the world. The economic development of Russia – that is, its late arrival to the stage of global capitalist development and the country’s subordination to the needs of global capital – was such that the bourgeoisie (remember Fanon?) could not play a progressive role in history: therefore, a more linear road to socialism through developments within a bourgeois revolution was out of the question.

“The incapacity of the bourgeoisie for political action,” wrote Trotsky

was immediately caused by its relation to the proletariat and the peasantry. It could not lead after it workers who stood hostile in their everyday life, and had so early learned to generalize their problems. But it was likewise incapable of leading after it the peasantry, because it was entangled in a web of interests with the landlords, and dreaded a shake-up of property relations in any form. The belatedness of the Russian revolution was thus not only a matter of chronology, but also of the social structure of the nation.Asked the future by Lenin (who remained skeptical of Trotsky’s ideas until the very last moment), Trotsky explained that the working class, in line with the peasants, was the only force capable of transforming Russian society. Furthermore, the only course of action was an immediate transition to socialism, skipping over the (clearly impossible) stage of capitalist development.

Crucially, the entire project hinges on the permanency of the revolution in a second sense: its ability to spread to countries outside of Russia. Decades before Stalin, Trotsky understood that socialism in one country was impossible. The workers’ movement is international, or it is nothing.

The necessity of a planned economy

Global capital, forever bound to its vampire-like task of consuming the lifeforce of the Sudanese people and the country’s natural resources, would like nothing more than a “free” and “stable” victim. Freedom and stability, of course, measured by the extent to which the country is malleable to the capitalist market. A typical solution put forward by a more liberal wing of the capitalist ideologs is exemplified in a proposal by Peter Woodward, who states that in order to bring stability to Sudan, a post-Bashir government must “clean up corruption; revive small-scale agriculture in the regions; restore health and education services; and attract investment for productive jobs for underemployed, educated young people who have been the backbone of the uprising.”

Yet, Woodward and his ilk live in a fantasy. What social force does Woodward imagine will bring about this transformation? A benevolent military? A (nonexistent) Sudanese bourgeoisie? The only force capable of transforming the Sudanese economy to meet the needs of the people is the Sudanese working class (80 percent of which is based in agriculture). Attracting investment means crushing labor and continuing to exploit natural resources. A workers’ government, in alliance with an international revolutionary movement, could refuse the dictates of austerity (à la Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso) and create planned economy designed to meet the needs of the African people - something the capitalist market is incapable of doing.

Independent class struggle

When history is written as it out to be written, it is the moderation and long patience of the masses at which men will wonder, not their ferocity.

- C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins

What the masterful Trinidadian socialist C.L.R. James wrote about the slaves of Haiti can be applied to the people of Sudan – just as it can be applied to the working class in the United States, China, and those laboring under capitalism in every corner of the globe. History promises nothing (some might add, except pain), but it does offer lessons and reveal trends.

What, then, can we learn from history as analyzed by a West Indian and Russian exile? The theory of permanent revolution would seem to be alive and well. It is crucial in understanding the revolutionary experience of less-developed, formerly colonized countries around the world. Neither the national bourgeoisie nor the military have anything to offer the masses of Sudan. If dictatorial rule is to fall, then socialism is the only way forward. No salvation lies in robust African capitalism – there is no freedom under wage slavery.

Perhaps most importantly, the Sudanese revolution must spread like wildfire! We repeat: The workers’ movement is international, or it is nothing. The struggle for freedom and an end to oppression in Sudan is the same fight waged in the streets of Algeria and Syria, the same struggle in Palestine and Ferguson, Missouri. Patient no longer, the ferocity of the masses will be truly astounding.

Comments

Post a Comment