Revolutionary Rehearsals: France 1968

(the boss needs you, you don't need him)

“The story of terrorism is written by the state and it is therefore highly instructive… compared with terrorism, everything else must be acceptable, or in any case more rational and democratic.”

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 1967.

"On Wednesday the undertakers went on strike. Now is not the time to die."

- Eyewitness to mass strike on May 14, 1968.

"The crisis was infinitely more serious and profound...it was not my position that was in question, it was general de Gaulle, the Fifth Republic, and, to a considerable extent, Republican rule itself."

- Prime minister Georges Popidou, May 25, 1968.

"May ’68 was the biggest mass upheaval in the history of France and the concurrent wildcat general strike was the most important strike in the history of the European workers movement since World War Two. Nowhere else was the rejection of the new model of consumerist life more profound, or so closely linked with the class struggle. Its impact reached every social category, wage earning sector, region and city in France, and lasted for years."

- Miguel Amoros

"May 1968 will enter the history of the class struggle as the month of the biggest revolutionary upsurge yet seen in an industrially developed capitalist country. Ten million workers on strike, all the big and medium-sized plants closed down, the most backward and least politically conscious layers of the proletariat and civil service employees brought into action, the technicians and foremen widely involved, the peasants joining the students and workers in the struggle, broader and broader and more and more militant demonstrations confronting the harried and increasingly demoralized forces of repression..."

- Statement by the International Committee of the Fourth International, June 10, 1968

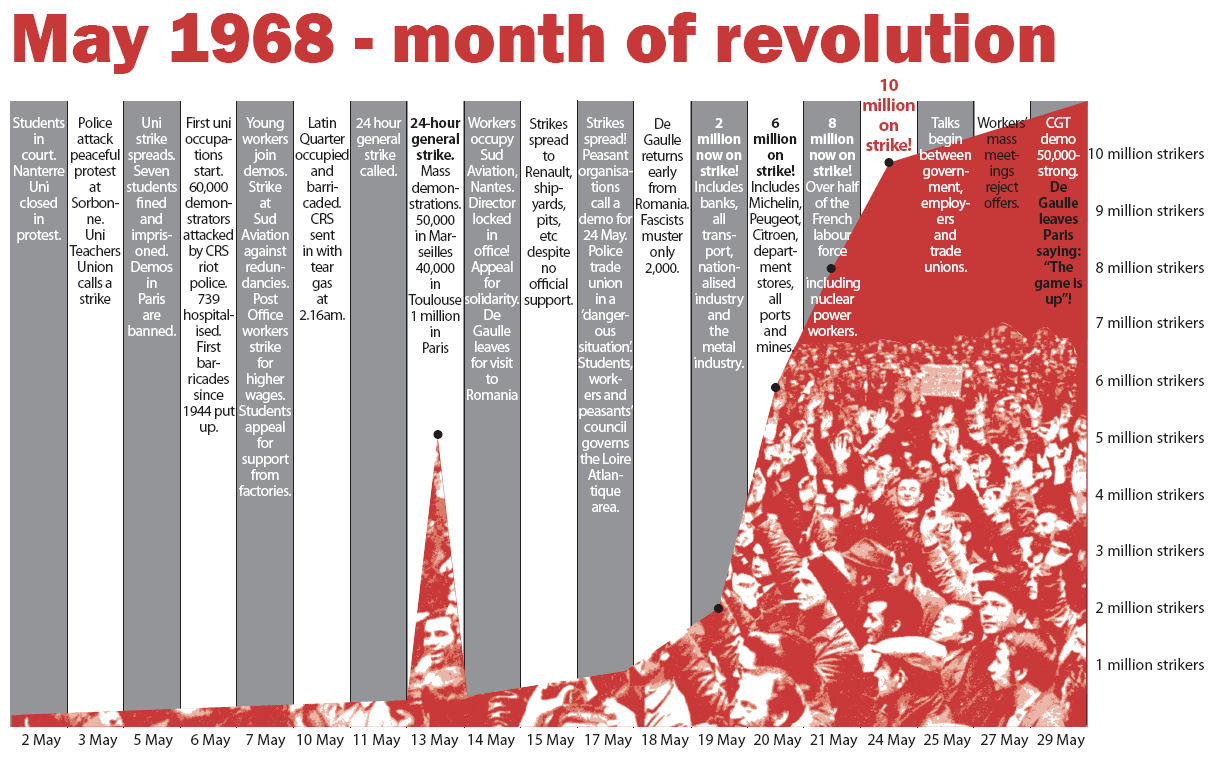

This is the first in a series of posts detailing the five "revolutionary rehearsals" recorded in Colin Barker's edited book by the same name. Ian Birchall wrote the section on France. On May 29, 1968, President Charles de Gaulle fled France, and over 10 million people (more than half of all workers in France) were on strike. How did it come to this point? How were de Gualle and French capitalism able to survive 1968 not only unscathed, but strengthened? I've compiled my notes and thoughts - along with a helpful and aesthetically pleasing timeline found on the internet - below. I've also added my own notes, thoughts, and expositions, especially around events leading up to May 1968.

Background

In 1871, the Paris Commune, perhaps the most significant event of the 19th century, erupts onto the pages of history. Barricades were erected, and the state was significantly transformed. The event greatly influences Marx and Engles, as described in Lenin's State and Revolution.

France was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940, and divided into a north and south. Free France, the government-in-exile, was led by Charles de Gaulle. Liberation was declared in 1945, and by 1968 French living standards were equivalent to those in Britain. The bourgeois papers reveled in the "pathetically weak trade unions" and pronounced the economy a "desirable balance between interventionist planning and the free market." Workers were increasingly under attack. In 1967, social security was reorganized, reducing workers' power and cutting reimbursement for medical expenses.

A series of strikes in 1947 involved 3 million "idled" workers and saw over 23 million working days lost (25,000 workers "idled" in the United States in 2017).

From 1954 to 1962, France waged war against the Algerian Nation Liberation Front (ALF) in the Algerian war of Independence (see, among other resources, The Battle of Algiers). When Algeria was declared independent in 1962, 900,000 European-Algerians fled to France within a few months. The war (and subsequent torture and mass murder) was a "moral corruption" that had "eaten away at the French state." On October 27, 1961, police in Paris attacked and killed 200 Algerian demonstrators, with dead bodies reportedly floating down the River Seine.

(Algeria won independence from France in 1962)

French colonial rule in Vietnam eroded in 1954 after the battle of Dien Bien Phu, and in February 1959, de Gaulle was elected president of the new Fifth Republic.

On October 9, 1967, Che Guevara was executed by forces operating under CIA agent Felix Rodriquez in Bolivia. His murder sparked outrage across the word, particularly on university campus.

The North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front (NLF) began the Tet offensive on January 30, 1968, exposing the weaknesses of US imperialism and the reality of the Vietnam War.

Students and academia

As in the United States, the number of university students exploded post-WWII. It's in the universities, writes Ian Birchal, that the "liberal mystique of education clashes with its social content [a capitalist social structure]." The International Socialist group (IS) wrote several accounts on education and students in a class-based society. "In the process of struggling," writes the IS

The student body itself is transformed. For the first time people find themselves shaping reality rather than being mechanically molded by it. The alienation from learning and debate that characterizes most students is replaced by an unprecedented desire and ability to learn. They reach inside themselves as if to draw out unnoticed qualities. The previous atomisation is replaced by a new feeling of purposeful self-activity. What so many of the students had wanted from education and found lacking—creativity, imagination, purpose, knowledge—is suddenly found in the struggle against the institutions of education. The lessons of 30 years are learnt in one day.

Many students in France opposed the Vietnam War and were drawn towards Cuba (liberated in 1959) and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. They opposed heavy conservatism (especially around matters of sexual freedom) in the university system, and were increasingly disillusioned at being unable to find work relevant to their studies after graduation.

If the working class constituted a ticking time bomb, implies Ian Birchal, then the students were the detonator.

Student agitation on the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris set events into motion.

Nanterre epitomized the contradictions of French capitalism and its higher education system. This was an overspill campus that strained with overwhelming student numbers just four years after opening. Beneath the self-congratulatory aura of progress and technology brought about by the post-war capitalist boom, life seemed hollow, with long hours and powerlessness at work or university, supposedly compensated for by consumer goods sold with saturation advertising. Side by side with the promise of prosperity were real squalor and poverty. Next door to the Nanterre campus was a huge shantytown inhabited by unskilled immigrant workers who labored in Paris’s engineering factories and on its building sites.Union leadership

Three unions stood out in French politics, representing some 3 million workers.

The General Confederation of Labor (CGT) was controlled by the Communist Party and concerned itself with a parliamentary road to socialism. Like the CP and its Stalinist residue, it can best be described as counter-revolutionary. The CGT will work in coordination with the capitalist state, particularly the French Communist Party (PCF) to deceive the workers and end the strikes.

The PCF was vehemently anti-revolutionary, and denounced the students as pseudo-leftists aiming the pollute the revolutionary minds of workers. It was above all concerned in the parliamentary road to socialism, and protecting the soviet union (thereby staying in favor with the major capitalist powers). The PCF worked to still "one of the greatest spontaneous movements in history."

The SFIO (Socialist Party) made no significant intervention. They were discredited as far as the masses were concerned for supporting de Gualle and the Algerian war.

The French Democratic Confederation of Labor (CFDT) aligned with the reformist left.

The General Confederation of Labor - Workers' Force (FO) was anti-communist.

As Birchall points out several times in his chapter, the trade unions, particularly the CGT, played a conservative role in the events of 1968. Time again, workers pushed beyond what the union leadership advocated.

The leaders of the major union federations and of the Communist Party were the ones who least wanted a successful revolution. If workers could take power in a developed industrial economy, they knew, it would inspire the workers of the Soviet Union to throw the parasitic bureaucracy off their backs...

Following months of conflicts between students and authorities at the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris, the administration shut down the university on May 2, 1968. Students protested and several were beaten and arrested.

The dance began on May 3 with the uprising of the Latin Quarter. The first barricades were built with bricks and burned cars on May 6. The street skirmishes continued during the following days, along with the burning of vehicles and the looting of stores. Workers, high school students and hoodlums from the outskirts of the city eagerly joined the fray. These elements soon outnumbered the university students. On the night of May 10, once all the stalling maneuvers of the new leaders and the old organizations had failed, more than sixty barricades were built. The leftist vanguardists vanished.

(May 10, the Night of the Barricades)

Turning to their usual tactic of diluting working class anger, the trade unions call for a one day strike on May 13. This totally backfires, as 1 million people march across Paris in the largest demonstration since liberation from the Nazis. "Every factory worker, every workplace seemed to be represented." The masses had seen their power and were not going to turn back. Workers were given a newfound sense of power, as “with the eating comes the appetite.”

"In some phases of the class struggle, confidence is more important than consciousness." The workers were conscious, but were given newfound confidence by the student protests and the mass movement stemming from them.

The general strike and mass demonstration on May 13 marked the transition from a student uprising to a working-class revolt.

On May 14, workers at the Sud Aviation factory in Nantes go on indefinite strike and occupy the factory, the first in what becomes a chain of workplace occupations.

These occupations were spontaneous in the sense that no central body called them, but very much planned and the result of hard work put in before hand in order to popularize the idea of a general strike and build solidarity amongst the workers. In one night, more than 9 million workers are on strike and, importantly, many were occupying their workplace.

The first night of the occupation of the Renault factory at Boulogne-Billancourt, the workers put up a large banner over the factory. It said, “For higher wages and better pensions.” The second day they took it down and they put up a new sign over the factory, which raised the traditional left-wing slogan, “For a Socialist Party-Communist Party-trade union government.” The third day they took it down and they put up another banner over the factory and it said, “For workers’ control of production.” In three days they had gone from higher wages to we should be running the show.Workers kept things running during the general strike. Water flowed, gas was distributed, mail was distributed. All of these services were organized by strike committees. "The necessities of life, normally taken for granted, mow appeared visibly as the products of human labor." Workers produced what they themselves considered important.

In most cases the strike committees were selected and imposed by the union bureaucracy. In only a few cases were the committees democratically elected. Those who the union could trust were selected, while revolutionary leftists were excluded.

In many cases the strike committee ensured the factory remained occupied with only a few people, and everyone else was sent home. There was no interested in drawing in the masses. In fact, it was avoided. "The factories, instead of being the fortresses of the working class, were often empty shells inhabited by a small clique of union functionaries."

An allegedly revolutionary party that allows the initiative to flow from below inevitably runs the risk of being driven beyond its original intentions. The alternative, chosen by the CGT and the Communist party, was to run a general strike in a more military fashion, from above. Trusted trade unionists were picked for strike committees and tried to get their policy endorsed. Mobilization of the workers was limited to the necessary minimum, to the numbers needed for such indispensable duties as picketing. Workers were allowed to drift home, while those who stayed in the factory were encouraged to play games rather than to indulge in dangerous debates. At moments one began to wonder whether the sit-down strike was designed to prepare the workers for the offensive or to isolate them from the outside world with its leftist germs.Instead of workers' councils (see Russia in 1917), there were action committees. They had no delegates or representatives, and no formal relation to the union organizations. Some were based in localities, others in workplaces, others were created only to mediate between workers and students. The did not have defined tasks, instead responding to the needs of the situation. Duties included clearing trash, fixing trams, organizing food supplies, producing information and propaganda, organizing street meetings, and producing artistic exhibits. Within these action committees there was not a discussion of taking state power.

In the last week of May, workers' organizations effectively ran the city of Nantes. Nantes was great, but there was no development of workers' control within the factories. Only the committees instituted by the union bureaucracy.

The radicalism of the students quickly infected young workers. And this radical upsurge infected other middle class elements of the population. These elements were flexible and would move only if there was a strong movement. If that movement died, they would retreat.

By the last week of May the strike had reached a critical juncture. It had to confront the capitalist state. What would be done about state power? How would the situation of dual power be resolved?

The workers continued to reject offers worked out between the government and the union bureaucracy. In this way they forced the union to continue the strike. But real power was never wrestled out of the union hands. The bureaucracy still controlled major sections of the movement.

The government concluded that only when the movement was on the decline could the armed bodies of the state be used to end the strike. Currently, the movement was too strong. And, there were signs of discontent and wavering among the police and soldiers.

There was friction between the prime minister and president. The state leaders were not united. De Gaulle flees to a French military base Germany for four days, where he meets with General Massu. Upon arrival, de Gaulle told the general, “Everything is fucked, the communists have provoked paralysis across the whole country. I’m in charge of nothing. There I’m retiring and as I feel threatened in France, my family too, I’ve come to find refuge with you, in order to decide what to do.” There was a power vacuum in France for four days, but the moment soon passed.

On May 30, de Gaulle broadcasts to the nation, calling for parliamentary elections. He makes semi-fascistic calls for supporters to use "extra-parliamentary measures" against the left. The PCF and reformists could not denounce such a call, because they believed in gaining power through parliament! One day later, 1 million people demonstrate in Paris in support of the government. Leftists are attacked.

"The reformists were so concerned with their parliamentary image that they kept on whining that it was leftist violence that was losing them votes; as a result the Gaullists were able to combine thuggery on the streets with the projection of a law and order image."Throughout June, a mix of concessions to workers and violence against strikers destroyed the movement. The CGT lied and deceived in order to get workers working, something many were reluctant to do.

The short film, Return to Work at the Wonder Factory, provides wonderful insight into the thinking of workers and union officials. "You can't have everything at once...step by step," repeats a union representative. "Look, don't say it's a victory," replies a worker.

And so the Communist Party leadership was successful after a period of some weeks in, as I said, breaking the general strike up into a bunch of small local strikes, and then winding down each occupation, one by one. They demoralized and manipulated workers in one plant to end their occupation by telling them that other factories were going back to work—because they wanted people back to work before the elections actually took place. The truth of the matter was this strike went as far as it could possibly go so long as it was spontaneous and leaderless. There was no alternative leadership to the trade unions and the Communist Party. It went as far as it could and then it was over.In the elections at the end of June, the Gaullists and their allies increased their parliamentary representation, and the PCF fell. The elections were rigged in many different ways, but this was secondary to the failures of the left.

The revolution was perhaps cultural, but failed as a political revolution capable of ending French capitalism.

A survey taken immediately after found that 20% of Frenchmen would have supported a revolution, 23% would have opposed it, and 57% would have avoided physical participation in the conflict. 33% would have fought a military intervention, while only 5% would have supported it and a majority of the country would have avoided any action.

The Situational International

The SI lasted from 1957 until 1972.

They rejected the idea that advanced capitalism's apparent successes—such as technological advancement, increased income, and increased leisure—could ever outweigh the social dysfunction and degradation of everyday life that it simultaneously inflicted.

The Situationist International was founded with the objective of formulating a revolutionary program within the domain of culture. The cultural revolution, understood as the subversion of everyday life under capitalism, was the creative complement of the social revolution.

The situationists not only insisted on the revolutionary will of the workers, although they never possessed the means to proclaim this publicly, they also did not hesitate to define May ’68 as a revolution. Unfinished, incomplete, without having fully unfolded all its content, without explicitly laying claim to this title, but it was, when all is said and done, a revolution after all. It is true that the State was not overthrown, but the same can be said of other revolutions.

Failures

- In the beginning stages, workers did not seize and control every state apparatus. Electricity could have been cut to disrupt opposition. The papers could have been seized directly (the CP paper slandered the students and manipulated the return to work).

- The working class never broke away from the reformist leadership.

- The working class was wrong to take on de Gaulle on the terrain of elections. Workers' power lies in the workplace, not the ballot box.

- Even a highly sophisticated advanced capitalist country can be thrown into question by the working class.

- The mass strike penetrates into every sector of society, and raises demands that go far beyond trade unionism.

- In the absence of a revolutionary leadership, reformists can regain control of even the most radical movements.

- Although the students provided a largely spontaneous trigger for a generalizing strike movement, spontaneity could not challenge the entrenched position of the bureaucracies of the PCF and CGT or mount a sustained challenge to the French state.

- People struggle for freedom in all kinds of ways. Revolution never looks quite the same; there is no formula for the revolution, or blueprint for how the masses will move. Revolutionary groups who demand the movement look a certain way do so at their peril.

- In What is to be Done?, Lenin writes that "the history of all countries shows that the working class, exclusively by its own efforts, is able to develop only trade-union consciousness." Was this proven to be the case in France? It seems in some ways yes, in others, no.

Comments

Post a Comment